I am perched on the balls of my feet, the arches painfully taut as I begin to trot on the bland gray carpeting. “Run,” says the doctor, his neck swiveling towards the hallway looming ahead of me. I scamper past the many open office doors on my invisible high heels.

I was diagnosed with Reflex Neurovascular Dystrophy at the Seattle Children’s Hospital in the spring of 1998. It is a rare condition that causes a malfunction of the body’s neurotransmitters, which, when functioning normally, send signals from your brain to your nerves.

The disease causes many issues that affect my daily life; I get tired very easily and my joints are often inflamed and sensitive to touch. I get stabbing pains in random areas of my body and during periods of high stress, I have deep spasms that build in my side until they release jolts of seizing pain up my neck. I have problems with body temperature, “brain fog,” and poor blood circulation.

Even on my good days, it can be difficult to walk by dinnertime.

The therapists spent six hours a day trying to reprogram my neurotransmitters during the summer of my diagnosis. It was known at the time that improved blood flow could reduce symptoms, so routine exercise was encouraged. The purpose of the physical therapy was to put my body in enough pain that it would force the neurotransmitters to function properly again, sending blood to the affected areas.

The results for many patients are mixed, and I unfortunately was not among the lucky ones. I did not see much, if any, improvement.

I tried and failed to keep up those exercises after leaving the facility. The hospital gave me a few occupational therapy tools, including a thick gob of red putty that I would stab with my fingers for hours. My parents lacked the time or discipline to help me maintai

n my daily therapy, but I attempted volleyball and high school band. I even participated in theater, eager to recapture the passion for dance that I’d tasted briefly as a child, only to experience disappointment as I failed to catch up to the other kids.

In general I lacked the structure in my life needed to make a long term commitment to my physical health, and over the years things only got worse.

But then Dance Central came into my life.

A RECEDING TIDE

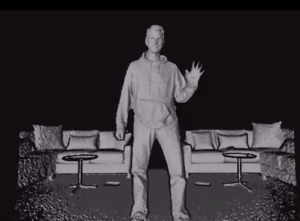

It’s been an interesting ride for motion control these past eight years. With the introduction of the Wii Remote in 2006, Nintendo managed to not only introduce the concept to a wide audience, but also make it non-threatening to people who would otherwise never play a “normal” video game. Even our grandparents were Wii Bowling.

The Kinect saw strong early support, but Microsoft’s recent decision to drop it as a requirement for the Xbox One reduces the peripheral to a mere afterthought. Virtual reality, particularly the combination of Oculus Rift and the Virtuix Omni treadmill, has potential, but the market for these devices is yet to be seen. And it has been years since I heard anything about the PlayStation Move.

Most people look at the brief rush of motion controls and the resulting move away as a natural thing; some even think getting rid of it altogether is a positive step forward. But I wonder, will the modern application of motion controls die as its relevance to gaming does?

AT HOME, SELF-MOTIVATED PHYSICAL THERAPY VIA DANCE

“I promise I’ll play it!” It’s 2010, and I am pleading with my boyfriend to buy me a Kinect for Christmas. The price tag would eat up his entire budget for my Christmas presents, but being disabled, unemployed, and very broke, I am persistent. “I can get fit indoors and I won’t be bored, I can play it almost every day!”

I had gained 60 pounds since moving to the Eastside. Leaving the comfort of Seattle proper changed my entire routine; I was no longer walking a few miles a day. My body had deteriorated so badly that my left femur was popping out of its pelvic socket. Going on long walks, which I did at night, when nobody could see me struggle, was helping a little, but I knew the next step was to push myself, and I couldn’t bear the thought of doing that in public.

Dance Central was immediately appealing because it looked as much fun as it was a workout. I figured at the very least I could improve my cardio to the point that I could go jogging in public. That was the personal goal I set, a symbol of the comfort I envied in able-bodied people.

But there was a part of me also very excited to recapture the ability and freedom I’d lost as a kid. I’d had to stop taking ballet in elementary school because my parents could no longer afford it, and by the time I could get instruction again in high school my body wasn’t in a condition to allow me to pursue it. It became something else I lost to my disease.

I persisted and my boyfriend relented. Dance Central became a weekly part of my life. I committed to twenty minutes a day three times a week, before slowly increasing my time. I could soon dance for close to an hour.

I played Dance Central 2 just as enthusiastically, thrilled with my progress. I built workouts that lasted a solid 50 minutes with the playlist feature. I lost all the weight I’d gained.

More importantly, I could move. Walking no longer felt like trying to wade through molasses, and my daily pain was reduced. I could sleep better, and I was less grouchy. My mobility improved on a daily basis. I still play Dance Central 3 to keep my fitness in check.

My struggles with physical therapy are not unique. The boredom is mind-numbing and motivation is hard to come by despite knowing how much it can help the pain. I’m fortunate to be able-bodied enough to put in a full body workout, and to have found a way to do so that works for me, as well as afford the technology.

There are still areas of my body that could use focus though, and it is here that my visions of what motion control could be turn lofty. My wrists, hands and fingers still need rehabilitation. I need specific exercises to condition my joints, guided repetition that will strengthen my muscle support and reduce the pain. The tracking technology of the Kinect seems to wield the most potential to address these issues. The voice controls alone provide huge benefits to people with a wide range of conditions and disabilities.

As support for the Kinect shifts away, will others get a chance to benefit from it as I have? I think of Harmonix, among the few studios to further motion control’s practical uses, and the serious blow that the dropped Kinect requirement for the Xbox One dealt. The decision comes ahead of Fantasia: Music Evolved, which promises to be one of the best offerings on the entire system.

Harmonix is now shouldered with the burden of trying to sell an accessory on top of a game. That Microsoft would do this to a studio that arguably carried the original Kinect sends a clear message to third party developers already wary of spending valuable resources on the unproven tech.

If the number of developers willing to incorporate innovative uses of motion control shrinks, will motion control’s uses, both practical and recreational, become a thing of the past? As a concept it will continue, but as the accessibility wanes, so too might the innovation. Without a market for these games, the added benefit to those who use them for physical therapy and fitness could dry up in the future.

The Kinect has already been used by scientists for a variety of purposes, from stroke recovery to improved medical imaging to working with children on the autism spectrum. I’m confident that medical technology is persistent and that researchers will continue to use the tools available, but the fewer low-cost and commercially available motion control solutions that exist the fewer the options become, especially for facilities with lower budgets.

Integrating new technology into our daily lives relies upon accessibility, affordability and ease of use. Where motion control is concerned, video games are the perfect Trojan horse.

Whatever the case I hold enormous hope for the future and how motion control might be used to benefit the physically impaired. We’ve already seen many advances due to the Nintendo Wii and the Kinect, technology that would have cost significantly more had its primary use not been entertainment. The video game industry has been a back door for amazing advances in physical therapy, and we risk losing that advantage if motion controls fade away.

Lately I’ve been walking down to Myrtle Edwards Park along the Seattle waterfront and running the path stretching the beach. My time on a 5K isn’t that great and by the end of the night I’ll still need a cane, but I don’t care.

It just feels good to move. It feels good to be free.

Inexpensive motion controls helped make that happen, and I don’t want to see the industry lose such a powerful tool for growth and health.